How the Jewish Apocalyptic Hope Was Recast in Church History

Introduction

In previous lessons, we introduced Paul within his historical setting—Second Temple Judaism—and outlined his native worldview, which is best described as Jewish apocalyptic. This worldview is apocalyptic in its conviction that history is moving toward a climactic end, divided into two ages. It is Jewish in its emphasis on the election of Israel and the administration of redemptive history through them.

In this session, we will pause from a focus on Paul in context and instead consider how Gentile narratives throughout Christian theological tradition have shifted over the centuries. Specifically, how they departed from that original first-century Jewish apocalyptic framework.

Competing Redemptive Narratives

In the first century, two alternative redemptive narratives competed with the Jewish apocalyptic one:

The Greek redemptive narrative, rooted in Platonic philosophy.

The Roman redemptive narrative, shaped by imperial ideology.

Since then, of course, church history has generated countless variations. Theologians, denominations, and sectarian movements have each developed their own redemptive schemas—answers to the question of what God has done, is doing, and will do. Yet, when viewed broadly, most Christian theological history can be grouped into three major streams: the Jewish, Greek, and Roman narratives.

Synthetic Narratives

Over time, these core narratives were blended into synthetic frameworks that have defined much of Christian theology:

The Augustinian narrative – a synthesis of Greek and Roman elements.

The dispensational narrative – combining Greek philosophy with aspects of the Jewish apocalyptic vision.

The inaugurational (or inaugurated) narrative – dominant in modern academic circles, blending Jewish and Roman ideas.

There are, of course, other non-Christian redemptive frameworks—Islamic, Hindu, naturalistic, and more—but within Christian tradition, these three remain the primary paradigms that continue to resurface throughout history.

The Jewish Apocalyptic Narrative

Our focus here is on the biblical Jewish apocalyptic worldview of Second Temple Judaism. While other Jewish streams arose—especially after the Bar Kokhba rebellion, when apocalyptic thought was suppressed within rabbinic circles—the biblical narrative can be summarized in two main features:

A monistic cosmology: Creation is a unified whole, composed of the earth below and multiple heavens above (described as three, five, seven, or ten in different traditions).

An apocalyptic soteriology: Salvation comes suddenly and climactically, dividing history into “this age” and “the age to come.”

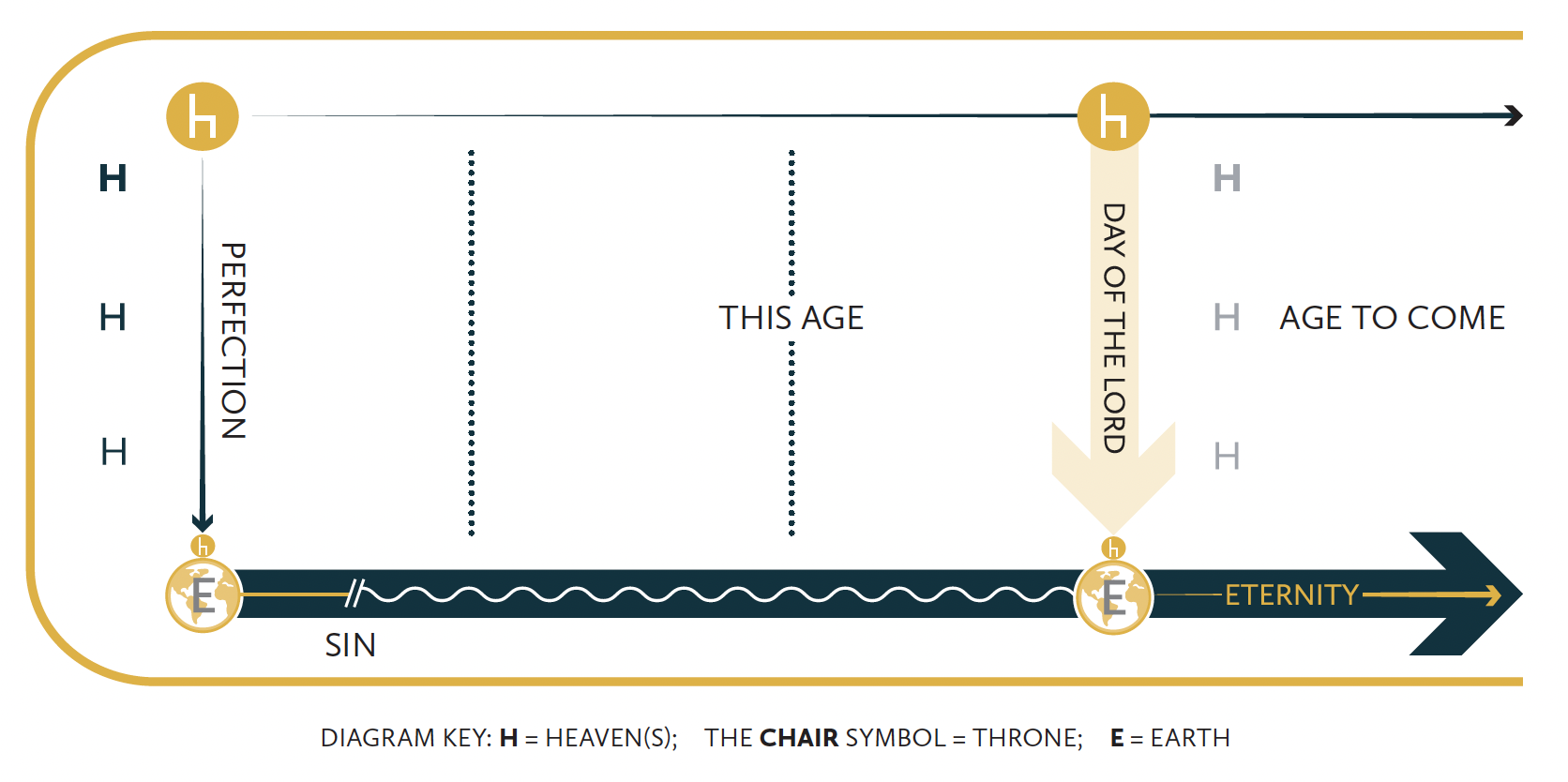

The diagram (adapted from The Gospel of Christ Crucified) below shows creation with God enthroned at the highest heaven, ruling over heaven and earth. Humanity, represented by Adam, was originally enthroned in Eden—the garden understood as a temple sanctuary mirroring the heavenly one. Sin fractured this relationship, unleashing death and turmoil, but history is moving linearly toward the “day of the Lord,” when God will bring radical reversal: resurrection, judgment, and the renewal of creation.

Key Features of the Jewish View

Linear time – Time is part of creation, with a beginning and a forward-moving trajectory. Eternity, in both Hebrew and Greek, is understood not as timelessness but as unending ages.

Continuity of creation – Eternal life is not a static, immaterial existence but an embodied life in a renewed heaven and earth, free of sin and death.

New creation expectation – The age to come includes bodily resurrection, judgment of the wicked, and the messianic kingdom centered in Jerusalem.

Darrell Bock and Craig Blasing summarize this perspective well in Three Views of the Millennium and Beyond, where Blasing contrasts it with the Greek model. He notes that the Jewish apocalyptic expectation affirms continuity: just as there is a heaven and earth now, so there will be a new heaven and new earth. Eternity is lived, embodied existence, not an abstract timelessness.

The Rise of the Greek Redemptive Narrative

In the late Second Temple period, Greek philosophical thought began spreading throughout the Greco-Roman world, especially as the Roman Empire consolidated power. This introduced a competing redemptive framework: the Greek redemptive narrative, which rests on a dualistic cosmology.

Whereas ancient Jews viewed the universe as a unified whole (monistic cosmology) and time as a linear progression toward a climactic end, Greek thought reshaped both the structure of the universe and the meaning of time. This shift—beginning roughly 1,800–1,900 years ago, in the first few centuries after the New Testament—marked a decisive change in how people understood reality.

Dualistic Cosmology and Escapist Salvation

In the Greek narrative, the universe is divided into two realms:

The material world – corrupt, broken, and destined for destruction.

The immaterial world of forms – pure, ideal, and eternal.

Salvation, therefore, was not about God redeeming creation but about escaping it. The material world was seen as a prison for the soul, and death became the gateway to liberation.

Plato’s Phaedo illustrates this well. On the last day of his life, Socrates describes death not as an enemy to be defeated, but as the release of the soul from the “tomb” of the body. Enlightenment—the soul’s awakening to the immaterial realm—initiates salvation, and death consummates it.

This dualistic framework began to reshape Christian thought in the second century. Paula Fredriksen, a critical historical scholar, traces how the God of Israel was reinterpreted under Hellenistic influence. While her opening claims may be objectionable, her description of the theological transformation is helpful. She notes that by the mid-second century, theologians such as Valentinus, Marcion, and Justin Martyr were redefining the God of Israel within Platonic categories.

Fredriksen summarizes it this way:

Paul's Jewish identity, Acts tells us, was already being called into question by the early second century. In that same century, Paul's god underwent a similar identity crisis. The ethnicity of the high god shifted: God the Father lost his Jewish identity too. Though some pagans continued to identify the high god as the god of the Jews, educated ex-pagan Christian theologians increasingly thought otherwise. In the work of Valentinus (Flourished: ca. 130s–150s), of Marcion (Flourished: ca. 140s), and of Justin Martyr (Flourished: ca. 150s–160s), we can trace this process whereby God the father of Christ became no longer Jewish. The point of orientation shared by all three thinkers—a point fundamental to the theology of Middle Platonism-was that the highest god was radically transcendent and changeless, and that another, lower god, a demiurgos, organized the material cosmos. This demiurge, functioning as a metaphysical buffer, protected the high god's immutability, radical stability, and absolute perfection. It was he, not the high god, who arranged unstable matter into cosmos, "order." (Paula Fredriksen)

This “demiurge” became a recurring concept in Greek thought—a divine artisan who shaped the material world but was distinct from the supreme God.

Greek philosophy held that everything in the material world was merely a flawed copy of its perfect form in the immaterial realm. For example:

In the immaterial world exists the perfect form of a chair.

In the material world, we encounter only broken, uncomfortable, imperfect chairs.

The task of philosophy, then, was to awaken the soul to the reality of the higher forms, while the body and material existence were seen as obstacles to overcome.

Integration into Christian Theology

By the second century, Christian thinkers were increasingly reading the Judeo-Christian Scriptures through this Platonic lens. As Fredriksen highlights:

Valentinus developed early Gnostic theology, heavily shaped by Platonic dualism.

Marcion—also influenced by Gnostic ideas—prompted the church to solidify the New Testament canon in response to his teachings.

Justin Martyr tried to balance sympathy for the Jewish apocalyptic worldview with Platonic philosophy, but ultimately laid the groundwork for its rejection in favor of the Greek model.

Origen and the Alexandrian School

This trajectory reached a major turning point with Origen (Flourished: ca. 220s–250s CE), head of the catechetical school in Alexandria. Alexandria—one of the three great intellectual centers of the ancient Mediterranean, alongside Athens and Rome—became a hub of Christian theological development.

Origen, drawing deeply on Platonic philosophy, systematized the fusion of Greek thought with Christian theology. In doing so, he effectively transformed the redemptive narrative: moving it away from the Jewish apocalyptic vision of resurrection and renewal, and toward a Greek vision of spiritual ascent and escape from the material world.

Origen’s approach to Scripture was fundamentally dualistic. He argued that every text had both a physical interpretation—concerned with Israel, history, and the material world—and a spiritual interpretation—concerned with an immaterial, heavenly destiny. So when he interprets Paul, particularly in 1 Corinthians 15, he reads Paul through the lens of a Greek redemptive narrative.

Here is an example from his commentary:

Having sketched, then, so far as we could understand, these three opinions regarding the end of all things, and the supreme blessedness ... we must suppose that an incorporeal existence is possible, after all things have become subject to Christ, and through Christ to God the Father, when God will be all and in all ... then the bodily substance itself also being united to most pure and excellent spirits, and being changed into an ethereal condition in proportion to the quality or merits of those who assume it (according to the apostle's words, 'We also shall be changed'), will shine forth in splendour; or at least that when the fashion of those things which are seen passes away, and all corruption has been shaken off and cleansed away, and when the whole of the space occupied by this world, in which the spheres of the planets are said to be, has been left behind and beneath, then is reached the fixed abode of the pious and the good situated above that sphere, which is called non-wandering, as in a good land, in a land of the living, which will be inherited by the meek and gentle ... which is called truly and chiefly 'heaven, in which heaven and earth, the end and perfection of all things, may be safely and most confidently placed. (Origen)

In other words, Origen claims Paul teaches that the eschatological hope is incorporeal existence—a non-bodily, spiritual state.

The irony is striking: in 1 Corinthians 15, Paul is actually refuting opponents who deny bodily resurrection. Paul argues for an eternal, embodied existence on a renewed earth. Origen, however, interprets Paul in the opposite way—advocating for salvation as a release from the body into an incorporeal realm.

At the popular level, this translated into the familiar imagery of “heaven”: clouds, harps, angels, and an eternal sing-along. But Origen gave it a systematic theological foundation.

Origen continues:

“The bodily substance itself also being unified to most pure and excellent spirits, and being changed into an ethereal condition in proportion to the quality or merits of those who assume it, according to the apostle’s words, ‘we also shall be changed.’”

For Paul, “we shall be changed” means transformation into a glorified, immortal body—still corporeal, still human. For Origen, it means leaving behind physical existence altogether. Salvation becomes escape from the material world, not its redemption.

Origen describes salvation as passing beyond the visible cosmos, beyond the planetary spheres, into the immaterial realm he calls the “non-wandering heaven”. He even applies biblical language about the “land of the living” and the inheritance of the meek (from the Psalms) to this incorporeal realm.

Here, Origen reshapes the biblical worldview of a plurality of heavens into a single “heaven” divided into material and immaterial realms. This dualism, later expressed in Latin as naturalis et supranaturalis (natural and supernatural), was foreign to first-century Jews. For Origen, the material world is corruption itself, and salvation is liberation into the incorrupt immaterial realm.

The Broader Shift

This shift from a Jewish apocalyptic narrative to a Greek escapist one had massive consequences:

The return of Jesus and the day of the Lord were gradually marginalized in Christian thought. Instead of final judgment at the resurrection, judgment was now imagined to occur immediately at death—leading to the “pearly gates” imagery, with Peter deciding admission into heaven.

Time and eternity were redefined. For Plato, time was a corrupted reflection of timeless perfection in the immaterial realm. This idea carried over into theology, where eternity came to mean “timelessness” and God was imagined as existing outside of time. By contrast, the Jewish worldview understood eternity as unending time, unending ages. Scripture itself portrays time as linear, present in both heaven and earth, with God actively involved in history (e.g., heavenly councils in 1 Kings 22, silence in heaven in Revelation 8).

Thus, Origen and other early Greek theologians reinterpreted the Jewish Scriptures “spiritually”:

Eden became the spiritual Eden.

The promised land became the spiritual promised land.

The Davidic throne became the spiritual throne of Christ in heaven.

This spiritualizing hermeneutic systematically replaced the apocalyptic hope of resurrection, judgment, and a renewed creation with a Platonic vision of escape from the material world into a timeless, immaterial realm.

The Roman Redemptive Narrative

In the 4th century, a dramatic shift occurred with the emergence of a new redemptive narrative—the Roman redemptive narrative. While the Greek redemptive narrative remained dominant, the Roman model took shape after Constantine’s conversion and played a lasting, though subordinate, role in Christian theology.

The central figure here is Eusebius of Caesarea, Constantine’s court historian. Though best known for his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius’ most consequential works are The Life of Constantine and An Oration in Praise of Constantine. In these writings, he recounts Constantine’s reign and argues that his conversion marks the fulfillment of Jewish Scripture. For Eusebius, the Pax Romana—the Roman peace—was nothing less than the visible manifestation of God’s sovereignty on earth.

This fit naturally with the Roman worldview. Unlike the Greek gods, who embodied philosophical ideals, the Roman gods were tied closely to the state. They functioned as guardians and guarantors of Rome’s stability. Eusebius Christianized this idea: the one true God was now working through the Roman Empire to bring about redemption. In his theology, the restoration of creation was unfolding through redeemed political structures—the Empire itself.

Eusebius wrote in The Life of Constantine:

“Thus, by the express appointment of the same God, two routes of blessing—the Roman Empire and the doctrine of Christian piety—sprang up together for the benefit of men. In short, the ancient oracles and predictions of the prophets were fulfilled… [quoting Ps. 72, Zech. 9, and Isa. 2]. These words, predicted ages before in the Hebrew tongue, have received in our own day a visible fulfillment.”

For Eusebius, prophecies of universal peace and dominion—like Psalm 72’s “He shall have dominion from sea to sea” and Isaiah 2’s vision of swords beaten into plowshares—were fulfilled not in the messianic kingdom, but in the Roman Empire itself.

The Roman Narrative Simplified

Compared to the Greek model, the Roman redemptive narrative was more straightforward and easier to embrace at a popular level. It still assumed a split cosmos of material and immaterial realms, but its focus was clear: God’s sovereignty was revealed in history through Rome.

For Origen and the Greek narrative, the promises were fulfilled “spiritually” in the immaterial realm, realized at death.

For Eusebius and the Roman narrative, the promises were fulfilled politically and historically in the Pax Romana.

The Crisis and Augustine’s Synthesis

Of course, Eusebius could not foresee the Empire’s collapse in the following generations. When Rome fell into crisis, so did his theological framework. It was Augustine of Hippo who responded, producing the most influential synthesis in Christian history: The City of God.

In this monumental work, Augustine combined the Greek and Roman models. He identified the “City of God” with both:

A heavenly, immaterial reality (the Greek narrative).

An earthly, historical expression through Rome and later the Church (the Roman narrative).

The result was a twofold kingdom:

The Church militant on earth, manifesting God’s sovereignty in history.

The Church triumphant in heaven, the immaterial destiny of the soul.

This synthesis redefined the “Kingdom of God” as a spiritual-ecclesiastical reality, fundamentally different from the Jewish apocalyptic hope of a messianic kingdom in a renewed Jerusalem on a renewed earth.

The Middle Ages and the Loss of the Jewish Narrative

By the Middle Ages, this synthesis had hardened. The Jewish apocalyptic worldview was dismissed as myth or ridiculed as primitive. As Benedict Viviano notes in The Kingdom of God in History, medieval theology misunderstood the this-worldly, future dimension of the Kingdom of God because of three factors:

Ignorance of the Jewish apocalyptic background.

Platonizing influence—a longing for the immaterial, timeless realm of Greek thought.

The Augustinian transformation of the Kingdom into the Church militant (on earth) and triumphant (after death).

Later developments, such as the imperial ideology of Christendom under Charlemagne and Innocent III, were essentially extensions of Constantine’s model of divine sovereignty through empire.

Modern Reflections - The Long Tradition of Greek and Roman Narratives

As J.C. Becker observed, the history of eschatology in the Church has largely been a process of:

Spiritualization (Greek narrative: the Kingdom as the immaterial heaven).

Institutionalization (Roman narrative: the Kingdom as the Church’s rule on earth).

What was marginalized was the original Jewish apocalyptic hope: the Kingdom of God as the future, bodily resurrection and messianic reign on a renewed earth.

The history of Christian theology, in many ways, is the history of the Greek and Roman redemptive narratives being repeated, reinterpreted, and recapitulated. From the 2nd century onward—especially under the influence of Origen in Alexandria and Augustine in North Africa—these two frameworks became the dominant ways Christians explained redemption.

Greek Narrative: Salvation as escape into an immaterial heavenly destiny.

Roman Narrative: Salvation as God’s sovereignty expressed through political structures, first Rome, then the Church.

Together, these formed what became the Augustinian synthesis, and they defined Christian eschatology for over a millennium.

From the condemnation of Montanism in the 2nd century to the supposed exclusion of chiliasm (apocalyptic millennialism) at the Council of Ephesus in 431—and later, its rejection in the Augsburg Confession of the Reformers—the Jewish apocalyptic hope was steadily marginalized.

The Reformation

The Protestant Reformation reclaimed the cross and justification by faith as the center of theology. But when it came to the second coming and eschatology, the Reformers largely left the Augustinian, Greco-Roman framework untouched.

Lutheran tradition leaned heavily on the Greek narrative: the cross secures entry into a heavenly destiny. This emphasis ran through German Pietism (Spener, Francke), the Moravian movement (Zinzendorf), into John Wesley’s revivalism, and eventually American evangelicalism and Billy Graham. In all these, the cross was preached primarily as the way to attain heaven.

Reformed tradition gave more weight to the Roman narrative: the kingdom of God expressed on earth through a Christian society. Calvin’s Geneva became the model for a utopian, God-governed community. This thread later shaped Dutch Reformed thought, came to America through Calvin College and Grand Rapids, and influenced Reconstructionist and Dominionist theology.

Both streams held to the Augustinian synthesis, but their emphases differed: heavenly destiny in the Lutheran tradition, redeemed social order in the Reformed tradition.

Discipleship Expressions

Throughout history, these two narratives shaped discipleship in distinct ways:

Greek narrative → Monasticism. If the material world is corrupt, the true disciple flees it through asceticism. Monasticism became the “new martyrdom”—a spiritual death to the world. From Egypt to Europe, Benedictine monasteries carried this ethos. Monks and nuns were seen as the “athletes of Christ,” the truest disciples.

Roman narrative → Ecclesiastical power. Here discipleship meant expanding the influence of the Church in the world, even by force. The Crusades epitomized this “Church militant” mentality. Dominionism and political Christianity carried the same impulse.

Thus, escapism and crusaderism became the twin discipleship responses—sometimes in conflict, sometimes reinforcing each other.

The Jewish Narrative’s Interruption

The Jewish apocalyptic narrative never disappeared entirely. It resurfaced in revival movements, reformations, and renewal efforts that sought to “get back to the Bible.” Sometimes these came through monastic or pietistic movements. In these flashes, the hope of bodily resurrection and the renewal of Jerusalem briefly re-emerged—but always against the tide of Greek and Roman dominance.

The 19th Century: Dispensationalism

A true break came in the late 19th century with dispensationalism, the first major movement to reject the Augustinian synthesis.

Dispensationalism proposed a dual redemptive plan: one for Israel on earth (Jewish/apocalyptic), and one for the Church in heaven (Greek/immaterial). History was divided into dispensations in which these two plans interacted.

Lewis Sperry Chafer, first president of Dallas Theological Seminary, summarized it:

“The dispensationalist believes that throughout the ages God is pursuing two distinct purposes: one related to the earth, with earthly people and earthly objectives; the other related to heaven, with heavenly people and heavenly objectives… When the Scriptures designate an earthly people who go on as such into eternity, and a heavenly people who abide in their heavenly calling forever, why should this be deemed incredible?”

This framework gave dispensationalism its defining features:

Israel as the earthly people with an earthly destiny.

The Church as the heavenly people with a heavenly destiny.

This distinction, however, is foreign to Scripture. Biblically, the contrasts are between Jew and Gentile, and between righteous and wicked. Both Jew and Gentile, redeemed by grace, share in the same hope: the resurrection of the dead and the inheritance of the new heavens and new earth.

Still, dispensationalism marked an important step. It reclaimed the Jewish narrative at a popular level—even if imperfectly—by insisting on Israel’s ongoing role in God’s plan.

Criticism and Adaptation

Reformed critics in the mid-20th century pushed back hard, especially against the “two plans of salvation.” This pressure shifted dispensational thought toward chiliasm (millennialism). The millennium in Revelation 20 became the arena in which the Jewish and Greek narratives played out together. Some dispensationalists emphasized a literal thousand-year reign (chiliasm), while others allowed for a two-age framework without it.

Over time, dispensationalism narrowed into a synthesis of Jewish apocalypticism plus Greek dualism, with the “secret rapture” (removing the Church to heaven) and a restored Jewish plan on earth.

The Inaugurational Synthesis

The final major turn in Christian eschatology was the inaugurational synthesis. Sparked by 19th–20th century scholarship on Jewish apocalypticism (especially German critical scholars), and countered by English theologians, this birthed the now-familiar debate between consistent apocalyptic (futurist) and realized eschatology (already/not-yet).

The inaugurational worldview (or “inaugurated eschatology”) took shape in the mid-20th century, emerging first in Europe during and after World War II and spreading into American evangelicalism in the 1960s and 70s.

At its core, it combines:

The Roman redemptive narrative (history as a progressive manifestation of divine sovereignty), and

The Jewish apocalyptic narrative from the late Second Temple period.

This synthesis redefined “the kingdom of God” and reshaped Christian eschatology for modern evangelical thought.

George Eldon Ladd, the scholar most responsible for introducing European scholarship to American evangelicals, articulated the inaugurational perspective. In one of his early works he wrote:

“The history of the kingdom of God is therefore the history of redemption viewed from the aspect of God’s sovereign or kingly power.”

The difficulty, however, is that in late Second Temple Judaism the “kingdom of God” did not mean generic divine sovereignty. Instead, it referred to a specific eschatological hope: the Messianic kingdom established through the Day of the Lord, judgment, resurrection, and the great banquet in Jerusalem.

While the Hebrew Scriptures (Tanakh) often use God’s reign in a broad sense of sovereignty, by the late prophetic and apocalyptic period—especially in Daniel—the phrase had come to mean something much more concrete and climactic.

Ladd went on to argue that God’s reign could be partially realized in “mediatorial stages” throughout history, manifesting progressively before its ultimate fulfillment in the age to come. Here, the Roman narrative of progressive sovereignty was layered onto the Jewish two-age framework.

But this blending introduces problems. In Jewish apocalyptic thought, the two ages are not simply different degrees of the same divine activity. They are fundamentally distinct:

This age: characterized by divine patience and restraint—“days of mercy,” as 1 Enoch 60 puts it. God withholds judgment to allow repentance.

The age to come: defined by judgment, restoration, and the full exercise of God’s kingly power.

If we collapse these distinctions into a single progressive manifestation of sovereignty, we dissolve the Jewish apocalyptic narrative. The first and second comings of Christ are reinterpreted not within the framework of mercy now and judgment later, but as stages in one continuous process.

Ladd leaned heavily on Oscar Cullmann, the French-German scholar who, in his 1948 book Christ and Time, used the analogy of D-Day and V-Day. The first coming of Christ was the decisive landing at Normandy (D-Day), establishing a beachhead of God’s reign. Church history is the ongoing campaign, leading to final victory at Christ’s return (V-Day).

While compelling as an illustration, this model assumes a single divine purpose at work throughout history. It flattens the two-age framework and obscures the unique significance of the cross and resurrection within the apocalyptic narrative:

The cross = God’s mercy in this age, shielding believers from wrath.

The resurrection = the promise of eternal life in the age to come.

By homogenizing God’s activity across both ages, inaugurated eschatology redefines the meaning of the first coming in light of the second.

Already / Not Yet vs. Jewish Apocalyptic

From this perspective came the now-familiar “already / not yet” paradigm. But the problem is that this continuum does not do justice to the Second Temple Jewish context. You cannot separate the “kingdom of God” from the rest of the apocalyptic package (Day of the Lord, resurrection, judgment, restoration). They all stand or fall together.

Thus, it makes little sense to say:

The kingdom has been inaugurated,

but the resurrection, judgment, and Day of the Lord have not.

For Jews of the first century period, these were inseparable events.

A Better Continuum

Instead of “already / not yet,” the more accurate continuum is:

Jewish / apocalyptic ←→ Non-Jewish / non-apocalyptic.

Christian theology across history can be seen as moving along this spectrum. Some traditions remained partially apocalyptic but less Jewish (e.g., certain 2nd-century fathers), while others became thoroughly non-Jewish and non-apocalyptic (e.g., Eusebius). Renewal movements have typically pushed theology back toward a more Jewish, apocalyptic orientation.

The anchor point for evaluating all of this must be the historical context of late Second Temple Judaism. Deviating from that context inevitably reshapes the meaning of the gospel itself.

The Inadequacy of Inaugurated Eschatology

Inaugurated eschatology struggles against two realities:

The package nature of Jewish apocalyptic hope. You cannot inaugurate one element (the kingdom) without the others (resurrection, judgment, restoration).

The present state of the world. Despite claims of realized sovereignty, the world remains profoundly unredeemed—something even casual observation confirms. Jewish scholars have rightly pointed out that this mismatch undermines the idea that the kingdom has “already” come in any meaningful way.

Yes, God still reveals Himself in this age through smaller theophanies, just as He did in biblical history. But the grand theophany—the Day of the Lord, resurrection, and the enthronement of Messiah in Jerusalem—remains future.

Looking Ahead

This lesson may feel heavy, but the issues are not as complex as they seem. Most of church history can be understood as a series of deviations from, or returns toward, the original Jewish apocalyptic narrative.

In a future lesson we will return to Paul—not as he has often been used to support synthetic redemptive narratives, but in his own historical context. We will examine how the death of the Messiah functioned within that apocalyptic framework, and how Paul discipled Gentiles accordingly.

References

This study draws on John Harrigan’s teaching, Discipling Gentiles into the Hope of Israel.