Ephesians 1

Paul’s Audience in Ephesus

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, To the saints who are in Ephesus, and are faithful in Christ Jesus: (Ephesians 1:1, ESV Bible)

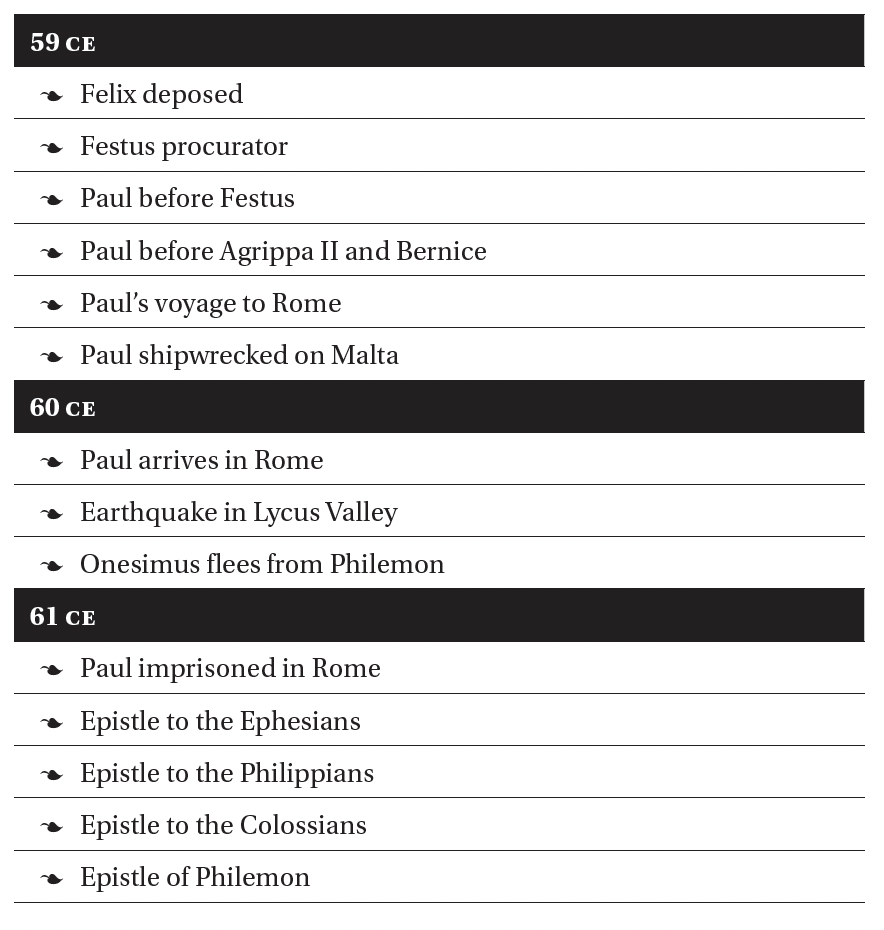

We count Ephesians among Paul’s so-called prison letters—a series of writings sent from Rome during his first imprisonment. He opens it “to the saints who are in Ephesus,” addressing a large body of Gentile disciples spread across house fellowships and synagogue gatherings in this bustling city. Thanks to Luke’s account in Acts (Acts 18-28), we know more about Paul’s ministry in Ephesus than in almost any other city.

By the time of writing, however, Paul could not return there, even had he been free. During the infamous Ephesian riots, when idol-worshipers stormed the streets shouting, “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” (Acts 19:21–41), Paul became an unwelcome person. Later, on his way to Jerusalem, he summoned the elders of Ephesus to meet him at Miletus rather than risk stepping foot back in the city (Acts 20:17). Other Jewish laborers in the gospel had also moved on: Apollos, once a teacher in Ephesus, had departed; Priscilla and Aquila, who for a time hosted a congregation in their home, had returned to Rome.

In Paul’s absence, his disciple Timothy carried the responsibility of shepherding the believers in Ephesus. Around the same period, the apostle John was also making his way toward Asia Minor and would eventually reside in the city. Though the leadership was Jewish, the majority of believers in Ephesus were Gentiles. It is to these Gentile disciples that Paul directs his words: “the saints who are in Ephesus, and are faithful in Christ Jesus.”

The term saints means “holy ones”—those set apart from the rest of humanity by their allegiance to Messiah Yeshua. To be “faithful in Christ Jesus” is to be loyal to Him: believing that He is the Messianic King, living under His authority, obeying His commandments, and heeding His words. In short, Paul’s greeting identifies the Ephesian believers as men and women consecrated to God through their steadfast loyalty to King Jesus.

Salutation

Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. (Ephesians 1:2, ESV Bible)

Paul greets the believers with a blessing, extending to them God’s abundant favor—His grace—and the gift of peace. In keeping with Yeshua’s own teaching, he addresses God as “our Father.” The grace Paul invokes is the very grace secured through Messiah Yeshua, God’s beloved Son, who, through His righteousness and suffering, obtained such an overflowing measure of divine favor that it may now be shared with all His disciples. Likewise, Paul pronounces peace upon them, not as a vague wish, but through the authority of the Prince of Peace Himself, in whose name and rule true shalom is given.

The Long Blessing

4 even as he chose us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and blameless before him. In love 5 he predestined us for adoption to himself as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will, 6 to the praise of his glorious grace, with which he has blessed us in the Beloved. (Ephesians 1:4-6, ESV Bible)

After the salutation, Paul opens the epistle with a blessing framed in the familiar pattern of a berachah: “Blessed be God who has done such and such.” Here, however, God is described in a unique way—“the God and Father of our Master Yeshua the Messiah.” Of all the divine titles available, this is the most precious to us as Yeshua’s disciples. A traditional berachah would call Him “King of the Universe,” a truth that rightly applies to all creation and expresses the universal relationship every creature has to God. But Paul selects a more intimate title, one that applies uniquely to Yeshua and to those who know God through Him. He is not only Creator and Sovereign of heaven and earth; He is the God and Father of our Master Yeshua.

As the letter unfolds, however, attention to the pronouns becomes essential. Paul writes that God has “blessed us in Messiah with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places” and that He “chose us in Him before the foundation of the world.” But who are the “we” and the “us”?

Many readers assume that Paul is speaking of all believers in general. Yet a closer reading shows otherwise. Beginning in verse 13, Paul shifts: “In Him you also, when you heard the word of truth … believed in Him.” This distinction between “we” and “you” is not accidental—it is central to understanding both Ephesians and Paul’s theology as a whole.

Paul consistently uses “we” to speak of the Jewish disciples of Yeshua—the apostolic community, the apostles themselves, and all the Jewish believers. In contrast, “you” designates the Gentile disciples. Recognizing this distinction is key. Ephesians is not tied to a single local controversy; instead, it presents a sweeping theological vision. For that reason, many scholars believe this letter was meant as a circular epistle, carried by Tychicus, to be read in multiple assemblies throughout Asia Minor. It offers a concise summary of Paul’s theology of distinction: the relationship of Gentile disciples to the Jewish people and to the kingdom of God.

Thus, at least in the opening chapters, Paul speaks self-consciously as a Jew, as an apostle, and as a representative of the Jewish disciples of Yeshua. But more broadly, he also speaks as one who represents Israel itself. In Paul’s theology, the Jewish disciples are like the leaven that leavens the whole lump, the holy root that sanctifies the entire tree. Their faith in Yeshua is a foretaste of Israel’s destiny. For Paul, it is only a matter of time until the wider Jewish people come to share that same conviction. Accordingly, when Paul says “we,” he speaks with Israel’s voice in distinction from the Gentile disciples who are now being grafted in.

What Advantage Has the Jew?

In his opening blessing, Paul makes a series of sweeping claims on behalf of the Jewish disciples of Yeshua—claims which, within his broader theology, ultimately encompass the entire nation of Israel. The first three are as follows:

God has blessed the Jewish people in Messiah with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places.

He chose the Jewish people before the foundation of the world to be holy and blameless.

In love, He predestined the Jewish people for adoption to Himself as sons through Yeshua the Messiah.

At first glance, one might conclude that these statements apply only to Jewish believers—that it is specifically the Jewish disciples of Yeshua who are blessed with every spiritual blessing, chosen before the foundation of the world, and predestined for adoption. Yet when Paul’s worldview is read against the backdrop of first-century Judaism, it becomes more likely that he is making claims about all Israel, even if the messianic fullness of these promises presently rests only on the “firstfruits”—the apostles and the early Jewish disciples of Yeshua.

1. Spiritual blessings. These blessings are the very ones promised to Israel in the Torah. Though not yet realized in their fullness as material blessings in this world—since redemption has not yet come—Paul affirms that they are already secured in Messiah and presently manifest in the heavenly realm.

2. Chosen people. Israel is called “the chosen people” because God set them apart from all nations. Jewish tradition teaches that even before the creation of heaven and earth, God chose Abraham and his descendants. He consecrated Israel to be holy—as recited in the Kiddush, “He has chosen us and sanctified us”—and blameless, assured through the promise of forgiveness: “Their sins and lawless deeds I will remember no more” (Jeremiah 31:34).

3. Adoption as sons. Israel was predestined for adoption through Yeshua. Messiah’s mission itself was directed toward this purpose, as Yeshua declared, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 15:24), and as Peter proclaimed, “The promise is for you and for your children” (Acts 2:39). Thus God calls Israel His “son”: “Out of Egypt I called my son” (Hosea 11:1), “Israel is my firstborn son … Let my son go, that he may serve me” (Exod 4:22–23), and “He avenges the blood of His children” (Deut 32:43).

In short, Paul is affirming that these blessings, privileges, and callings belong first and foremost to Israel—the Jewish people—not to the Gentiles. God has “blessed us in the Beloved,” meaning that Israel is blessed in the merit of Messiah. Israel is the people chosen before the foundation of the world. Israel is predestined to adoption as God’s sons. In this passage Paul speaks with striking boldness, almost flaunting the privileged status of Israel in Messiah. As a Jew, a disciple of Yeshua, and an apostle, he rhetorically elevates the dignity of his people—and the verses that follow only amplify this exalted position.

Redemption of Israel

Paul continues his discourse about the Jewish people:

7 In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of his grace, 8 which he lavished upon us, in all wisdom and insight. (Ephesians 1:7-8, ESV Bible)

Paul is indeed speaking of the Jewish disciples of Yeshua; yet these disciples are but the firstfruits of what the prophets promised: the full redemption of all Israel in the age to come. The term redemption carries a double sense—it speaks both of personal spiritual deliverance and of national restoration, which will reach its fulfillment when Messiah returns. And whom does Messiah come to redeem? He comes to redeem Israel.

How will this redemption be accomplished? It is through the merit of His suffering, which secured an abundance of grace and favor from God sufficient to cover Israel’s sins and trespasses, and to bring an end to her punishments—the exile, the covenant curses, and the yoke of foreign dominion. The blood of Messiah is His very life, poured out on behalf of the nation, as He endured death on a Roman cross in order to purchase forgiveness and secure redemption.

This is why Peter could stand before his fellow Jews and proclaim: “Repent and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit. For the promise is for you and for your children” (Acts 2:38–39). Paul likewise declares that Messiah’s death obtained such an overflowing abundance of divine favor that there is more than enough to lavish the riches of His grace upon Israel.

The Mystery of His Will

8 which he lavished upon us, in all wisdom and insight 9 making known to us the mystery of his will, according to his purpose, which he set forth in Christ 10 as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth. (Ephesians 1:8-10, ESV Bible)

In Ephesians 1:8–10, Paul invokes what we might call the mystical triad of chochmah, binah, and da‘at—“wisdom, insight, and knowledge.” These are the very spheres where God’s Spirit intersects human consciousness. Through them, God has disclosed His hidden will, “according to His purpose, which He set forth in Messiah as a plan for the fullness of time.” Once again, this revelation is entrusted to the same “us” mentioned in the preceding verses—that is, to Israel.

This divine plan is no late development. It has been in place since the very beginning—even before creation itself. Its scope is universal: “to unite all things in Messiah, things in heaven and things on earth.” This reflects a deeply Jewish vision of the end of days—the final consummation when all things are brought into visible unity under God. Nothing in creation is random, nothing is wasted. All things are already held together in Him, though hidden for now, and will one day be revealed in fullness through the work of Messiah.

And to whom was this plan first made known in wisdom, insight, and knowledge? To the Jewish people. By the Spirit of God through chochmah, binah, and da‘at—and through the prophetic voice of Torah and the Scriptures of Israel—this mystery was revealed. The events of Yeshua’s ministry were not unforeseen interruptions, but the very fulfillment of what Israel’s prophets had long foretold. As representatives of Israel, Paul, the apostles, and the Jewish disciples of Yeshua stand as the appointed stewards of that revelation.

The Inheritance of Israel

11 In him we have obtained an inheritance, having been predestined according to the purpose of him who works all things according to the counsel of his will, 12 so that we who were the first to hope in Christ might be to the praise of his glory. (Ephesians 1:11-12, ESV Bible)

Paul declares that in Messiah, “we”—that is, the Jewish people—have obtained an inheritance. This inheritance is nothing less than the covenantal promises given to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob: the land, the redemption, the kingdom, and even eternal life. These are the blessings recorded in the Torah and amplified by the prophets, passed down from the fathers to the sons.

He explains that this inheritance was predestined according to the sovereign will and purpose of God, to be brought to fulfillment through Messiah. Thus, “we who were the first to hope in Messiah” exist “to the praise of His glory.” This phrase, “the first to hope,” unmistakably refers to Israel—the people who had been anticipating the arrival of the eschatological King long before the New Testament era. Yet Paul also has in view the Jewish disciples and apostles, who placed their hope specifically in Yeshua and therefore stand as the firstfruits of Israel’s long-awaited hope. These Messianic Jews, as representatives of the nation, validate Messiah’s identity and bear witness to His glory.

In doing so, Paul sets up the structure of his letter. His opening doxology establishes two groups: “we,” the Jews (and more precisely, the Jewish disciples of Yeshua), and “you,” the Gentiles who have joined themselves to Israel through allegiance to Yeshua, the Messiah of Israel. Later in the letter, Paul will insist that these two groups are not divided in the kingdom of God, for there is “one body and one Spirit … one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God” (Eph 4:4–6). This unity echoes his statement in Galatians 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Yet it is crucial to note that Paul begins by distinguishing Jew from Gentile. This rhetorical framing is not contradicted by the later call to unity; rather, it provides the necessary foundation for understanding his theology of distinction. For Paul, spiritual oneness does not erase Israel’s role. Instead, it affirms that the unique inheritance of Israel has now become the means by which Gentiles, too, share in the praise of Messiah’s glory.

What About Gentile Disciples?

13 In him you also, when you heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and believed in him, were sealed with the promised Holy Spirit, 14 who is the guarantee of our inheritance until we acquire possession of it, to the praise of his glory. (Ephesians 1:13-14, ESV Bible)

The phrase “you also” marks a decisive shift in Paul’s address. He now turns from the Jewish disciples to the Gentile disciples of Yeshua. While his immediate audience is the non-Jewish believers in Ephesus, Paul’s role as the “apostle to the Gentiles” (Romans 11:13), combined with the universal scope of his theology here, widens the horizon to include all Gentile followers of Yeshua. If any doubt remains about his audience, passages like Ephesians 2:11 and 3:1 make it clear that Paul is addressing Gentile believers.

The “word of truth” they heard was the gospel of salvation—the good news that they, too, could share in redemption through Israel’s Messiah. When they believed, they transferred their allegiance to him, acknowledging him as King and Lord, placing their trust and hope in him with lives of obedience. This was no small shift; for Gentile believers in the first century, it meant turning away from the dominant loyalty demanded by Rome and its emperor—very likely Nero at the time—and pledging loyalty instead to the crucified and risen Messiah of Israel.

In that transfer of allegiance, they received the “promised Holy Spirit”—a down payment, a pledge of the coming Messianic Age. Paul surely had in mind Joel 2:28: “I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh.” The Spirit was not promised only to Israel but to all nations. Thus, Gentile disciples stand as the firstfruits of that universal outpouring, sharing equally with Jewish disciples in the foretaste of the kingdom.

Both Jews and Gentiles, sealed by the same Spirit, now bear within themselves the guarantee of the inheritance. That inheritance—the kingdom of God on earth, the Messianic Era—remains future, just as it was in Paul’s day. Yet even now, the Spirit functions as a pledge and down payment of what is to come, “to the praise of his glory.” In other words, this shared experience of the Spirit testifies to Messiah’s identity and vindicates his authority.

The pattern confirms the story: the Jewish disciples first received this pledge when the Spirit was poured out in Acts 2 at Shavu‘ot in the Temple. The Gentile disciples received the same Spirit in Acts 8 in Samaria, and again in Acts 10 in the house of Cornelius the centurion. Since then, the Spirit has continued to be poured out upon all who place their trust in Yeshua—Jew and Gentile alike—each outpouring proclaiming the same truth: Messiah’s glory is vindicated, and his kingdom is sure.

To the Jew First and also to the Greek

Paul is a Jew speaking out of the story of Israel. His entire gospel is rooted in the Hebrew Scriptures and God’s covenantal promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. When he says “we” in Ephesians 1:1–12, he is speaking as one of those heirs — a Jew who belongs to the covenant people who first received God’s promises. Israel was chosen to be the vessel of God’s revelation to the world (cf. Deut 7:6–8; Amos 3:2).

Thus, when Paul frames salvation history, it always begins with Israel, because that is the way God structured His plan. Messiah is the fulfillment of Israel’s story, not a departure from it.

Messiah’s mission was first and foremost to Israel. As Jesus himself declared, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 15:24). His earthly ministry was concentrated among the Jewish people, demonstrating God’s faithfulness to His covenant promises. Likewise, the apostles were Jews. The first disciples, the early church leaders, and those who received the Spirit at Pentecost were all Jewish (Acts 2). Paul reinforces this Jewish foundation when he affirms in Romans 9:4–5 that the covenants, the adoption, the glory, the law, the worship, the promises, and even the Messiah himself belong to Israel.

Yet the plan of God was never limited to Israel alone. The extension of the gospel to the Gentiles was not an afterthought or “plan B”; it was built into the very fabric of the Abrahamic covenant. From the beginning, God had declared to Abraham, “in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen 12:3). Israel was to be the first recipient of God’s covenant blessings, the “firstborn son” of the nations (Exod 4:22). Through Israel, the blessings were to flow outward, extending to all peoples. This is why Paul can describe Gentile believers as wild olive branches grafted into the cultivated olive tree of Israel’s promises (Romans 11:17–24). In Ephesians 1:13, when Paul shifts with the phrase “you also,” he signals that the Gentiles are now participants in these same covenant blessings through their connection to Messiah.

Paul’s message, then, is not that the Gentiles have replaced Israel but that they have been joined to Israel. The language of Scripture consistently supports this: Gentiles who were once alienated are now “brought near” and made “fellow citizens” with the saints of Israel (Ephesians 2:12–13). Paul states it plainly in Ephesians 3:6: “Gentiles are fellow heirs, members of the same body, and partakers of the promise in Christ Jesus through the gospel.” They do not displace Israel; rather, they share in Israel’s promises by being joined to the covenant God made with Abraham and his descendants.

This entire pattern is captured in Paul’s famous declaration in Romans 1:16: “I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek.” The gospel was revealed first to Israel, and through Israel it was extended to the nations. To the Jew first: Israel received the covenant, the Messiah, and the Spirit. And also to the Greek: the Gentiles now share in this salvation, but only as those who have been grafted into Israel’s story, not as a replacement or a separate entity.

A Prayer for Gentile Disciples

15 For this reason, because I have heard of your faith in the Lord Jesus and your love toward all the saints, 16 I do not cease to give thanks for you, remembering you in my prayers, 17 that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give you the Spirit of wisdom and of revelation in the knowledge of him, 18 having the eyes of your hearts enlightened, that you may know what is the hope to which he has called you, what are the riches of his glorious inheritance in the saints, 19 and what is the immeasurable greatness of his power toward us who believe, according to the working of his great might 20 that he worked in Christ when he raised him from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places, 21 far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come. 22 And he put all things under his feet and gave him as head over all things to the church, 23 which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all. (Ephesians 1:15-18, ESV Bible)

The Gentile disciples demonstrated their allegiance to Yeshua through their love toward all the saints. For this, Paul’s first response is gratitude: “I do not cease to give thanks for you.” Yet his prayer does not stop with thanksgiving. He also petitions God to grant them deeper spiritual insight—to open “the eyes of their hearts.” Through the Spirit of God, he asks that they might receive an additional measure of wisdom, revelation, and knowledge (chochmah, binah, and da’at) so that their inner eyes would be enlightened.

In Hebrew idiom, the “heart” represents the mind, the seat of thought and understanding. Thus, Paul implies that the Gentile disciples are failing to grasp something essential. His prayer is that God would remove the veil and allow them to see clearly. But what is it that they need to see?

Paul answers with three great truths:

The hope to which God has called you.

The riches of his glorious inheritance in the saints.

The immeasurable greatness of his power toward us who believe.

He elaborates that this power is the very same power God displayed in raising Yeshua from the dead, seating him at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above every ruler, authority, power, and dominion, and giving him the name above every name. All things have been placed under his feet, and he has been appointed head over all things for the sake of his body, the community of disciples, which is his fullness—the one who fills all in all (Ephesians 1:18–23).

Paul’s concern for the Gentile believers is clear. Though they have faith in Messiah, love for the saints, and steadfast devotion, they are still missing critical dimensions of God’s redemptive plan. They do not yet fully understand the hope to which they are called, the richness of the inheritance that is theirs, or the greatness of God’s power at work on their behalf.

The rest of the epistle is devoted to unpacking these three themes. Paul seeks to broaden the horizons of his Gentile audience—men and women who had once lived as idolaters, estranged from the God of Israel—so that they might perceive the grandeur of God’s plan of redemption and recognize the unique role they now play within it.

Rule for all the Communities

In the chapters that follow, Paul works hard to impress upon the Ephesian disciples the extraordinary implications of their place as non-Jewish followers of Yeshua. His concern is clear: they have not fully embraced their new spiritual identity.

In the opening chapter, Paul highlights the unique privileges of being Jewish—having Israel’s incomparable heritage and covenantal promises fulfilled through Messiah. Yet he quickly pivots to his concern for the Gentile disciples. Many of them seemed to feel that God’s promises did not truly apply to them. To belong, to be fully included, they assumed they had to shed their Gentile identity and become Jewish.

Paul confronts this same issue in Galatians and, indeed, across all his congregations. Wherever he planted the gospel, Gentile disciples often gravitated toward Jewish identity, envying the heritage of their Jewish brothers and sisters. Paul therefore found himself repeatedly urging them to remain Gentiles and to value the identity God had given them. He summarized this principle as his rule for all the churches:

“This is my rule in all the churches. Was anyone at the time of his call already circumcised? Let him not seek to remove the marks of circumcision. Was anyone at the time of his call uncircumcised? Let him not seek circumcision.” (1 Corinthians 7:17–18)

In first-century shorthand, “circumcision” referred to Jewish identity. Restated, Paul’s meaning is this: If you were called as a Jew, remain Jewish. If you were called as a Gentile, remain Gentile. Exceptions existed—such as intermarriage (where Jewish law required conversion for the non-Jewish spouse) or for individuals with Jewish ancestry reconciling their identity—but apart from those circumstances, Paul’s answer was firm: Gentiles should not become Jews.

This struggle mirrors the sociological dynamic in today’s Messianic Jewish movement more closely than in any other modern context. Just as in Paul’s day, Gentiles who attach themselves to a Jewish environment often feel a sense of disenfranchisement. Traditional Christian theology resolved this tension differently: by the second century, replacement theology had gained dominance, teaching that Christian identity erases and supersedes all prior distinctions. Under this system, Jewish believers ceased to be Jewish, Gentile believers ceased to be Gentile, and both were collapsed into a homogenized “third race”—the Christian.

But that was not Paul’s message. Replacement theology is a distortion that has obscured Paul’s teaching for nearly two thousand years. Paul’s answer to Gentile insecurity was not to erase Jewish-Gentile distinction, but rather to pray that God would open the eyes of the Gentile disciples’ hearts so that they might grasp three essential truths:

The hope to which he has called you.

The riches of his glorious inheritance in the saints.

The immeasurable greatness of his power toward all who believe.

Before moving forward, we should pause to reflect on these three points. They are not only for the Ephesians but for all disciples—Jewish and Gentile alike—and they reveal the ultimate goal of salvation in Yeshua.

The hope to which he has called you

The language of being “called” is a hallmark of Paul’s teaching, and it echoes the way the Master personally summoned his disciples. He called Simon Peter and his brother Andrew, saying, “Follow me.” He called James and John, the sons of Zebedee, with the same invitation: “Follow me.” Each disciple was confronted with a personal summons to surrender his life to the path of discipleship.

For Paul, that same call continues in every generation. Yeshua calls both Jew and Gentile whenever they hear the good news and are invited into discipleship. This understanding explains Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 7:18: “Was anyone at the time of his call already circumcised? … Was anyone at the time of his call uncircumcised?” To be called is, quite simply, to be called to become a disciple of Yeshua.

Thus, “the hope to which he has called you” refers to the great hope bound up in that call: the redemption, the kingdom, the resurrection of the dead, and a share in the World to Come. Yeshua himself confirmed this when he said, “All that the Father gives me will come to me, and whoever comes to me I will never cast out … and this is the will of him who sent me, that I should lose nothing of all that he has given me, but raise it up on the last day” (John 6:37–39).

That is the hope of the calling—the promise of resurrection and eternal life in the age to come.

2. The Riches of His Glorious Inheritance in the Saints

This inheritance refers specifically to the covenantal promises given to the children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—the foundational assurances God made to the patriarchs. At first glance, one would assume such an inheritance belonged exclusively to the Jewish people, the children of Israel. Yet Paul explains that through their union with Yeshua, Gentile disciples have become “fellow heirs” with Israel, sharing in these same promises.

The promises begin in Genesis 12: blessing for those who bless Israel and curse for those who oppose her. They include the gift of the land and the promise of a great nation—destined to reach its fullness in the Messianic Era. They encompass the vision of Abraham as the father of many nations and extend ultimately to the hope of the New Jerusalem, which Abraham himself glimpsed from afar.

These covenantal promises form the backbone of the Torah and are expanded upon by the prophets throughout the Tanakh. They are Israel’s heritage—but in Messiah, they have also become the inheritance of those called from among the nations. This is the glorious inheritance Paul speaks of, the one we share with his holy people.

3. The Immeasurable Greatness of His Power

This passage points directly to the resurrection of the dead, the ultimate demonstration of God’s gevurah (power). Jewish tradition makes this very connection in the second blessing of the Amidah, recited daily in the synagogue: God’s might is revealed in His power to raise the dead.

You are mighty forever, O Lord.

You revive the dead; You are great to save.You cause the wind to blow and the rain to fall.

You sustain the living with kindness,

revive the dead with great mercy,

support the fallen, heal the sick,

free the bound,

and keep faith with those who sleep in the dust.Who is like You, Master of mighty deeds?

Who can be compared to You—

King who brings death and restores life,

and makes salvation sprout?Faithful are You to revive the dead.

Blessed are You, O Lord, who revives the dead.(Amidah, second blessing (Gevurot) – the blessing of God’s might and resurrection)

Paul illustrates the measure of this power by describing Messiah’s resurrection, ascension, and enthronement. By this immeasurable power, God raised Yeshua from the dead, exalted his human body into the heavenly realms, and seated him at His right hand. There He was granted authority above every created being and spiritual power—whether angels or demons, visible or invisible—above every name, not only in this present age but also in the age to come.

The apostles understood this as the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy: “Behold, my servant shall act wisely; he shall be high and lifted up, and shall be exalted” (Isaiah 52:13). In this exalted place, Yeshua embodies “the fullness of him who fills all in all.” That is, he is filled with the very fullness of God.

God’s power is not simply the ability to bring life from death; it is the power to transform mortality into immortality, the finite into the infinite, the earthly into the divine. This is the immeasurable greatness of God’s might in Messiah.

The ultimate goal, as Paul stated earlier, is “to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth” (Ephesians 1:10). Through the risen Messiah, the whole cosmos—matter and spirit, time and space—is being infused with God’s own presence. Reality itself is being reshaped, drawn into union with Yeshua, until he fills all things in every way. Though we can scarcely fathom this mystery, it means that creation itself is being subsumed into the Messiah.

As Paul elsewhere declares: “Even though we once regarded Messiah according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer” (2 Corinthians 5:16). The Yeshua known in weakness and mortality has now been raised in glory, placed above all things, and given as head over all creation to his community of disciples—his body. In him, the universe has been united and brought under his authority, and astonishingly, he has been given to us.

Not According to the Flesh

Here we encounter one of the very issues Paul feared his Gentile readers might be missing—especially when they found themselves fretting about whether or not they were Jewish. The apostle to the Gentiles was weary of this flesh-level obsession with status and prestige, this endless self-doubt and second-class anxiety. That is why he prayed so earnestly that the eyes of their hearts might be opened: that they would not merely comprehend these truths, but know them deeply—the hope to which God had called them, the riches of their inheritance among the saints, and the immeasurable greatness of God’s power.

Daniel Lancaster paraphrases Paul’s intent: “If you truly grasped the full implications of your salvation through Yeshua, you would not waste a thought on status, prestige, ancestry, or social class—for who you are as his disciple transcends them all.”

This is not a new thought. The rabbis taught that if Israel had not sinned with the golden calf, they would have attained immortality and divinity, as the psalm declares: “I said, ‘You are gods, sons of the Most High, all of you’” (Psalm 82:6). But in sin, they forfeited that status: “Nevertheless, like men you shall die, and fall like any prince” (Psalm 82:7). In a similar vein, when Yeshua’s opponents accused him of blasphemy—“because you, being a man, make yourself God” (John 10:33)—he answered by citing the very same psalm: “If he called them gods to whom the word of God came—and Scripture cannot be broken—do you say of him whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world, ‘You are blaspheming,’ because I said, ‘I am the Son of God’?” (John 10:34–36).

Likewise, Paul declares that God has predestined Israel “for adoption to himself as sons” (Ephesians 1:5). Gentile disciples are not excluded but welcomed into this destiny, equal participants in the inheritance.

Admittedly, these are lofty, mystical truths, not easily reduced to plain, manageable categories. Paul himself never watered them down. It is enough to recognize his point: our identity in Messiah has been lifted to such heights—so far beyond pride, ego, social caste, and human approval—that the distinctions between Jew and Gentile, while real, pale in comparison.

This does not mean that Gentiles have become Jews, or that the distinction between Jew and Gentile has been erased. If that were the case, much of Paul’s argument across his letters would make no sense. It does mean, however, that Gentile disciples must stop thinking of themselves as “just Gentiles.” They must have the eyes of their hearts opened to recognize the profound meaning of their salvation—an identity rooted not in human categories, but in their union with the Messiah, in whom all things are being brought together.